Asymptote

In analytic geometry, an asymptote ( /ˈæsɪmptoʊt/) of a curve is a line such that the distance between the curve and the line approaches zero as they tend to infinity. Some sources include the requirement that the curve may not cross the line infinitely often, but this is unusual for modern authors.[1] In some contexts, such as algebraic geometry, an asymptote is defined as a line which is tangent to a curve at infinity.[2][3]

The word asymptote is derived from the Greek ἀσύμπτωτος (asímptotos) which means "not falling together," from ἀ priv. + σύν "together" + πτωτ-ός "fallen."[4] The term was introduced by Apollonius of Perga in his work on conic sections, but in contrast to its modern meaning, he used it to mean any line that does not intersect the given curve.[5]

There are potentially three kinds of asymptotes: horizontal, vertical and oblique asymptotes. For curves given by the graph of a function y = ƒ(x), horizontal asymptotes are horizontal lines that the graph of the function approaches as x tends to +∞ or −∞. Vertical asymptotes are vertical lines near which the function grows without bound.

More generally, one curve is a curvilinear asymptote of another (as opposed to a linear asymptote) if the distance between the two curves tends to zero as they tend to infinity, although usually the term asymptote by itself is reserved for linear asymptotes.

Asymptotes convey information about the behavior of curves in the large, and determining the asymptotes of a function is an important step in sketching its graph.[6] The study of asymptotes of functions, construed in a broad sense, forms a part of the subject of asymptotic analysis.

Contents |

A simple example

The idea that a curve may come arbitrarily close to a line without actually becoming the same may seem counter to everyday experience. The representations of a line and a curve as marks on a piece of paper or as pixels on a computer screen have a positive width. So if they were to be extended far enough they would seem to merge together, at least as far as the eye could discern. But these are physical representations of the corresponding mathematical entities; the line and the curve are idealized concepts whose width is 0 (see Line). Therefore the understanding of the idea of an asymptote requires an effort of reason rather than experience.

Consider the graph of the equation y=1/x shown to the right. The coordinates of the points on the curve are of the form (x, 1/x) where x is a number other than 0. For example, the graph contains the points (1, 1), (2, 0.5), (5, 0.2), (10, 0.1), ... As the values of x become larger and larger, say 100, 1000, 10,000 ..., putting them far to the right of the illustration, the corresponding values of y, .01, .001, .0001, ..., become infinitesimal relative to the scale shown. But no matter how large x becomes, its reciprocal 1/x is never 0, so the curve never actually touches the x-axis. Similarly, as the values of x become smaller and smaller, say .01, .001, .0001, ..., making them infinitesimal relative to the scale shown, the corresponding values of y, 100, 1000, 10,000 ..., become larger and larger. So the curve extends farther and farther upward as it comes closer and closer to the y-axis. Thus, both the x and y-axes are asymptotes of the curve. These ideas are part of the basis of concept of a limit in mathematics, and this connection is explained more fully below.[7]

Asymptotes of functions

The asymptotes most commonly encountered in the study of calculus are of curves of the form y = ƒ(x). These can be computed using limits and classified into horizontal, vertical and oblique asymptotes depending on its orientation. Horizontal asymptotes are horizontal lines that the graph of the function approaches as x tends to +∞ or −∞. As the name indicate they are parallel to the x-axis. Vertical asymptotes are vertical lines (perpendicular to the x-axis) near which the function grows without bound. Oblique asymptotes are diagonal lines so that the difference between the curve and the line approaches 0 as x tends to +∞ or −∞. More general type of asymptotes can be defined in this case.

Vertical asymptotes

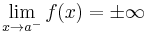

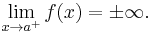

The line x = a is a vertical asymptote of the graph of the function y = ƒ(x) if at least one of the following statements is true:

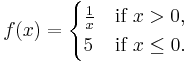

The function ƒ(x) may or may not be defined at a, and its precise value at the point x = a does not affect the asymptote. For example, for the function

has a limit of +∞ as x → 0+, ƒ(x) has the vertical asymptote x = 0, even though ƒ(0) = 5. The graph of this function does intersect the vertical asymptote once, at (0,5). It is impossible for the graph of a function to intersect a vertical asymptote (or a vertical line in general) in more than one point.

Horizontal asymptotes

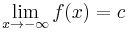

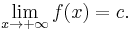

Horizontal asymptotes are horizontal lines that the graph of the function approaches as x → ±∞. The horizontal line y = c is a horizontal asymptote of the function y = ƒ(x) if

or

or

In the first case, ƒ(x) has y = c as asymptote when x tends to −∞, and in the second that ƒ(x) has y = c as an asymptote as x tends to +∞

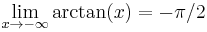

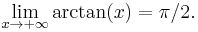

For example the arctangent function satisfies

and

and

So the line y = −π/2 is a horizontal tangent for the arctangent when x tends to −∞, and y = π/2 is a horizontal tangent for the arctangent when x tends to +∞.

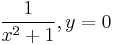

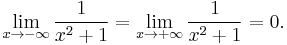

Functions may lack horizontal asymptotes on either or both sides, or may have one horizontal asymptote that is the same in both directions. For example, the function ƒ(x) = 1/(x2+1) has a horizontal asymptote at y = 0 when x tends both to −∞ and +∞ because, respectively,

Oblique asymptotes

When a linear asymptote is not parallel to the x- or y-axis, it is called an oblique asymptote or slant asymptote. A function f(x) is asymptotic to the straight line y = mx + n (m ≠ 0) if

![\lim_{x \to %2B\infty}\left[ f(x)-(mx%2Bn)\right] = 0 \, \mbox{ or } \lim_{x \to -\infty}\left[ f(x)-(mx%2Bn)\right] = 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/039e49d4c1d857678f1a24c10471bde1.png)

In the first case the line y = mx + n is an oblique asymptote of ƒ(x) when x tends to +∞, and in the second case the line y = mx + n is an oblique asymptote of ƒ(x) when x tends to −∞

An example is ƒ(x) = x−1/x, which has the oblique asymptote y = x (m = 1, n = 0) as seen in the limits

Elementary methods for identifying asymptotes

Asymptotes of many elementary functions can be found without the explicit use of limits (although the derivations of such methods typically use limits).

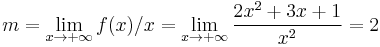

General computation of oblique asymptotes for functions

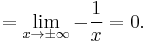

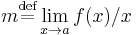

The oblique asymptote, for the function f(x), will be given by the equation y=mx+n. The value for m is computed first and is given by

where a is either  or

or  depending on the case being studied. It is good practice to treat the two cases separately. If this limit doesn't exist then there is no oblique asymptote in that direction.

depending on the case being studied. It is good practice to treat the two cases separately. If this limit doesn't exist then there is no oblique asymptote in that direction.

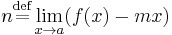

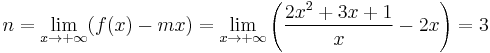

Having m then the value for n can be computed by

where a should be the same value used before. If this limit fails to exist then there is no oblique asymptote in that direction, even should the limit defining m exist. Otherwise y = mx + n is the oblique asymptote of ƒ(x) as x tends to a.

For example, the function ƒ(x) = (2x2 + 3x + 1)/x has

and then

and then

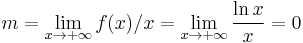

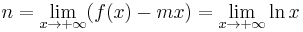

so that y = 2x + 3 is the asymptote of ƒ(x) when x tends to +∞. The function ƒ(x) = ln x has

and then

and then

, which does not exist.

, which does not exist.

So y = ln x does not have an asymptote when x tends to +∞.

Asymptotes for rational functions

A rational function has at most one horizontal asymptote or oblique (slant) asymptote, and possibly many vertical asymptotes.

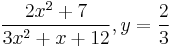

The degree of the numerator and degree of the denominator determine whether or not there are any horizontal or oblique asymptotes. The cases are tabulated below, where deg(numerator) is the degree of the numerator, and deg(denominator) is the degree of the denominator.

| deg(numerator) − deg(denominator) |

asymptotes | example asymptote |

|---|---|---|

| < 0 | y = 0 |  |

| = 0 | y = the ratio of leading coefficients |  |

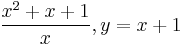

| = 1 | y = the quotient, in the long division of the fraction |  |

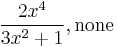

| > 1 | none |  |

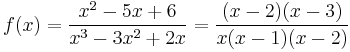

The vertical asymptotes occur only when the denominator is zero (If both the numerator and denominator are zero, the multiplicities of the zero are compared). For example, the following function has vertical asymptotes at x = 0, and x = 1, but not at x = 2.

Oblique asymptotes of rational functions

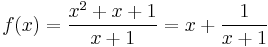

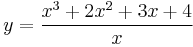

When the numerator of a rational function has degree exactly one greater than the denominator, the function has an oblique (slant) asymptote. The asymptote is the polynomial term after dividing the numerator and denominator. This phenomenon occurs because when dividing the fraction, there will be a linear term, and a remainder. For example, consider the function

shown to the right. As the value of x increases, f approaches the asymptote y = x. This is because the other term, y = 1/(x+1) becomes smaller.

If the degree of the numerator is more than 1 larger than the degree of the denominator, and the denominator does not divide the numerator, there will be a nonzero remainder that goes to zero as x increases, but the quotient will not be linear, and the function does not have an oblique asymptote.

Transformations of known functions

If a known function has an asymptote (such as y=0 for f(x)=ex), then the translations of it also have an asymptote.

- If x=a is a vertical asymptote of f(x), then x=a+h is a vertical asymptote of f(x-h)

- If y=c is a horizontal asymptote of f(x), then y=c+k is a horizontal asymptote of f(x)+k

If a known function has an asymptote, then the scaling of the function also have an asymptote.

- If y=ax+b is an asymptote of f(x), then y=cax+cb is an asymptote of cf(x)

For example, f(x)=ex-1+2 has horizontal asymptote y=0+2=2, and no vertical or oblique asymptotes.

General definition

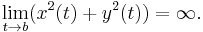

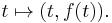

Let A : (a,b) → R2 be a parametric plane curve, in coordinates A(t) = (x(t),y(t)). Suppose that the curve tends to infinity, that is:

A line ℓ is an asymptote of A if the distance from the point A(t) to ℓ tends to zero as t → b.[8]

For example, the upper right branch of the curve y = 1/x can be defined parametrically as x = t, y = 1/t (where t>0). First, x → ∞ as t → ∞ and the distance from the curve to the x-axis is 1/t which approaches 0 as t → ∞. Therefore the x-axis is an asymptote of the curve. Also, y → ∞ as t → 0 from the right, and the distance between the curve and the y-axis is t which approaches 0 as t → 0. So the y-axis is also an asymptote. A similar argument shows that the lower left branch of the curve also has the same two lines as asymptotes.

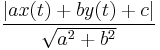

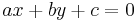

Although the definition here uses a parameterization of the curve, the notion of asymptote does not depend on the parameterization. In fact, if the equation of the line is  then the distance from the point A(t) = (x(t),y(t)) to the line is given by

then the distance from the point A(t) = (x(t),y(t)) to the line is given by

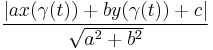

if γ(t) is a change of parameterization then the distance becomes

which tends to zero simultaneously as the previous expression.

An important case is when the curve is the graph of a real function (a function of one real variable and returning real values). The graph of the function y = ƒ(x) is the set of points of the plane with coordinates (x,ƒ(x)). For this, a parameterization is

This parameterization is to be considered over the open intervals (a,b), where a can be −∞ and b can be +∞.

An asymptote can be either vertical or non-vertical (oblique or horizontal). In the first case its equation is x = c, for some real number c. The non-vertical case has equation y = mx + n, where m and  are real numbers. All three types of asymptotes can be present at the same time in specific examples. Unlike asymptotes for curves that are graphs of functions, a general curve may have more than two non-vertical asymptotes, and may cross its vertical asymptotes more than once.

are real numbers. All three types of asymptotes can be present at the same time in specific examples. Unlike asymptotes for curves that are graphs of functions, a general curve may have more than two non-vertical asymptotes, and may cross its vertical asymptotes more than once.

Curvilinear asymptotes

Let A : (a,b) → R2 be a parametric plane curve, in coordinates A(t) = (x(t),y(t)), and B be another (unparameterized) curve. Suppose, as before, that the curve A tends to infinity. The curve B is a curvilinear asymptote of A if the shortest of the distance from the point A(t) to a point on B tends to zero as t → b. Sometimes B is simply referred to as an asymptote of A, when there is no risk of confusion with linear asymptotes.[9]

For example, the function

has a curvilinear asymptote y = x2 + 2x + 3, which is known as a parabolic asymptote because it is a parabola rather than a straight line.[10]

Asymptotes and curve sketching

The notion of asymptote is related to procedures of curve sketching. An asymptote serves as a guide line that serves to show the behavior of the curve towards infinity.[11] In order to get better approximations of the curve, asymptotes that are general curves have also been used [12] although the term asymptotic curve seems to be preferred.[13]

Algebraic curves

The asymptotes of an algebraic curve in the affine plane are the lines that are tangent to the projectivized curve through a point at infinity. Asymptotes are often considered only for real curves,[14] although they also make sense when defined in this way for curves over an arbitrary field.[15]

A plane curve of degree n intersects its asymptote at most at n−2 other points, by Bézout's theorem, as the intersection at infinity is of multiplicity at least two. For a conic, there are a pair of lines that do not intersect the conic at any complex point: these are the two asymptotes of the conic.

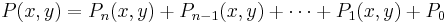

A plane algebraic curve is defined by an equation of the form P(x,y) = 0 where P is a polynomial of degree n

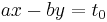

where Pk is homogeneous of degree k. Vanishing of the linear factors of the highest degree term Pn defines the asymptotes of the curve: if Pn(x,y) = (ax − by) Qn−1(x,y), then the line

is an asymptote, where t0 is chosen so that the curve and line meet at infinity. Over the complex numbers, Pn splits into linear factors, each of which defines an asymptote. However, over the reals, not only may Pn fail to split, but also if a linear factor has multiplicity greater than one, the resulting asymptote may be entirely spurious. For example, the curve x4 + y2 + 1 = 0 has no real points in the finite plane, but its highest order term gives the asymptote x = 0 with multiplicity 4.

Other uses of the term

|

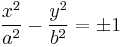

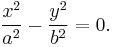

The hyperbolas have asymptotes The equation for the union of these two lines is |

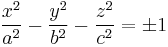

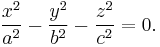

Similarly, the hyperboloids are said to have the asymptotic cone[16][17] The distance between the hyperboloid and cone approaches 0 as the distance from the origin approaches infinity. |

See also

References

General references:

- Kuptsov, L.P. (2001), "Asymptote", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=A/a013610

Specific references:

- ^ "Asymptotes" by Louis A. Talman

- ^ Williamson, Benjamin (1899), "Asymptotes", An elementary treatise on the differential calculus, http://books.google.com/?id=znsXAAAAYAAJ&pg=241

- ^ Nunemacher, Jeffrey (1999), "Asymptotes, Cubic Curves, and the Projective Plane", Mathematics Magazine 72 (3): 183–192, doi:10.2307/2690881, JSTOR 2690881

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989.

- ^ D.E. Smith, History of Mathematics, vol 2 Dover (1958) p. 318

- ^ Apostol, Tom M. (1967), Calculus, Vol. 1: One-Variable Calculus with an Introduction to Linear Algebra (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-00005-1, §4.18.

- ^ Reference for section: "Asymptote" The Penny Cyclopædia vol. 2, The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1841) Charles Knight and Co., London p. 541

- ^ Pogorelov, A. V. (1959), Differential geometry, Translated from the first Russian ed. by L. F. Boron, Groningen: P. Noordhoff N. V., MR0114163, §8.

- ^ Fowler, R. H. (1920), The elementary differential geometry of plane curves, Cambridge, University Press, ISBN 0486442772, http://www.archive.org/details/elementarydiffer00fowlrich, p. 89ff.

- ^ William Nicholson, The British enciclopaedia, or dictionary of arts and sciences; comprising an accurate and popular view of the present improved state of human knowledge, Vol. 5, 1809

- ^ Frost, P. An elementary treatise on curve tracing (1918) online

- ^ Fowler, R. H. The elementary differential geometry of plane curves Cambridge, University Press, 1920, pp 89ff.(online at archive.org)

- ^ Frost, P. An elementary treatise on curve tracing, 1918, page 5

- ^ Coolidge, Julian Lowell (1959), A treatise on algebraic plane curves, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 0486495760, MR0120551, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Kunz, Ernst (2005), Introduction to plane algebraic curves, Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston, ISBN 978-0-8176-4381-2; 978-0-8176-4381-2, MR2156630, p. 121.

- ^ L.P. Siceloff, G. Wentworth, D.E. Smith Analytic geometry (1922) p. 271

- ^ P. Frost Solid geometry (1875) This has a more general treatment of asymptotic surfaces.

![\lim_{x\to\pm\infty}\left[f(x)-x\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/21af6e89089fc39667d57d143d607879.png)

![=\lim_{x\to\pm\infty}\left[\frac{x^2-1}{x}-x\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/28fdd7947a9aa45543cb0b84bd3b3ed3.png)

![=\lim_{x\to\pm\infty}\left[(x-\frac{1}{x})-x\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/920ee937b7abd5703a7e678ea8bd33cd.png)